MOSUL — Ziyad loaded his wife and three children in the big German sedan that used to serve as his taxi between Baghdad and Mosul. That was in June 2014. The jihadists had just captured Iraq's second-largest city and Ziyad, built like a late-career wrestler, with a big smile and spoiled teeth, was fleeing towards the would-be safe territory of Iraqi Kurdistan.

"I looked for an apartment there," he recalls. "But it was way too expensive. Nothing for less than $500 a month."

A few days later, Ziyad, who refuses to give his whole name, decided to return to Mosul — and to the raging jihadist storm. There, he moved into the chic neighborhood of al-Muhandisin, where he'd been looking after his in-law's big house (in Iraq, an empty house is a plundered house).

Across the street, a new neighbor took up residence at the same time. The man moved into a residence accessible from the second floor, which is uncommon in Mosul. The staircase is surrounded by red sheets of metal, necessary visual protections in a city where looking inside your neighbor's courtyard is a serious no-no. Luxuriant orange trees overflow from the garden. A message on the wall of the house reads "property of the Islamic State."

Ziyad's new neighbor was medium-sized, slim, athletic and in his 30s. His jihadist guerrilla-fighter garb didn't hide the tattoos of what, people guessed, was a tumultuous past. His black hair framed a face on which he used to grow a trimmed beard — in violation of ISIS rules prohibiting men from shaving so as to fit as closely as possible with the fantasized image of the prophet Muhammad.

The man was boastful, and would compensate for his North-African accent and clumsy, overly literal Arabic with notable people skills. He was also French, though he answered to the jihadist pseudonym Abu Bakr al-Firansi.

"At first, I was wary of him. Foreign fighters had the right to life and death," says Ziyad. Mosul had just been conquered, and another Abu Bakr — ISIS leader al-Baghdadi — had proclaimed the restoration of the caliphate in Mosul's Great Mosque.

Taking over the neighborhood

Muhandisin, Mosul's most luxurious neighborhood, was a good capture. It sprang up in the 1980s and is ideally located near the forest that borders the Tigris River. Many Christians moved there. Huge houses that look like kitsch neo-Babylonian temples were built. There were also more modest homes, in less flashy places, along tree-lined streets and calm traffic lanes.

Beginning in the 1990s, the whole area was dominated by a gigantic shadow, that of a huge mosque. It was a pet project of Saddam Hussein and remains an unfinished mass of concrete. Work on the mosque ended with the 2003 U.S. invasion.

When ISIS seized Mosul and made the city its Iraqi capital, the some 50,000 Christians who were still living there fled. From one day to the next, Muhandisin lost half of its population. ISIS helped itself to the abandoned properties, transforming the neighborhood and installing its leaders and foreign fighters. Like Ziyad's new neighbor.

For them, we weren't human beings

The new residents covered exterior walls with sheets of metal to protect themselves from prying eyes. They established control centers, monitored the area with security cameras and set up underground weapons workshops where they manufacture their 120-millimeter shells.

A bureaucracy took shape. To go through check points, people needed to secure carbon-paper permission slips. The smallest expense, be it for weapons, munitions or walkie-talkies, was written down and archived. Women would come and go, silent shadows covered from head to toe, but often armed with Kalashnikovs. For ISIS, a man shouldn't have to hear the voice of a woman other than his wife.

The jihadist group also transformed society. It invented a caste system dominated by those who've sworn allegiance to ISIS, first among them foreign fighters and Iraqi leaders. The rest, the common people, the masses, were seen as a "herd" to be led by the "guide," Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

"They despised us, especially the Russian jihadists," Ziyad recalls. "For them, we weren't human beings. They wouldn't answer us when we would greet them with an 'As-salāmu ʿalaykum' (peace be with you)."

He describes al-Firansi as being "less harsh than the others" and recalls how the Frenchman "used to talk to everybody, make jokes, and spend time at the restaurant. He would parade in his BMW, listen to rap music, drift round the roundabouts. I even took the liberty to tell him to be careful. He replied, 'We are ISIS. We do what we want.'"

People even said al-Firensi smoked cigarettes. ISIS seemed to forgive his excesses, perhaps because of one of his exploits. Just after the jihadists had retaken Mosul, some 20 Kurdish fighters who'd been captured managed to escape. The Frenchman hunted them down successfully, one by one.

"French fighters had a better reputation than the others among the population. They were more open," an Iraqi military source says.

Yasser Ibrahim, a Muhandisin resident, recalls that several of them talked about their past: "They would tell us, 'In France, the police are after me. I'm a former bandit. I've tried everything, I've done everything. Everything except jihad.'"

Writing on the wall

Al-Firansi (which translates as "the Frenchman") was often away. What role he played exactly is unclear. "I know of at least four people by the name of Abu Bakr al-Firensi," a source in the Iraqi intelligence services says. "One of them was the manager of the Ninewa hotel, ISIS' luxury establishment. Without more details, it's impossible to know who yours is."

In March 2016, he took part in the battle of Fallujah. In Mosul, he trained the ashbal (lion cubs), children indoctrinated by ISIS to become the organization's next generation of ruthless fighters. With him he brought two brothers in arms — Abu Yacub al-Tunsi and Abu Moussa al-Senegali — both French.

The French wife grew impatient

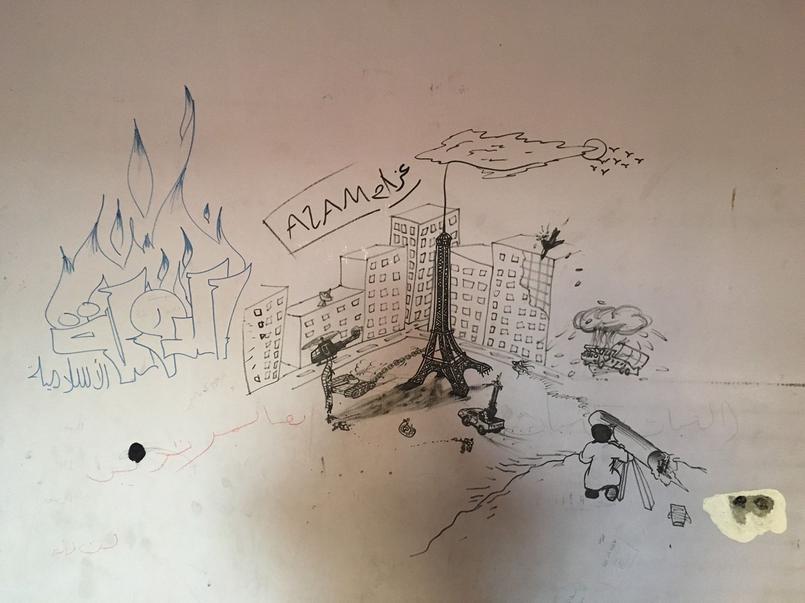

Inside his now deserted home, the walls of one room are covered with drawings, ominous and naive at the same time, that he signed with the name "Azam." One of them shows the Eiffel tower knocked down by a tank, car bombs exploding in front of blocks of flats and a jihadist firing a rocket. In another drawing, Azam wrote, "We've come to behead you," in not-quite perfect Arabic.

In an apocalyptic setting, an ISIS flag floats above a pickup truck that shoots down a burning warplane. A soldier is bleeding to death on the ground. In the foreground, a muscular jihadist poses, weapon in hand. His face is nothing but a dark mask. ISIS ideology bans this type of human representation.

As time went by, the Iraqi government's assault to retake Mosul was put in place, slowly. Air strikes eliminated jihadist leaders, one by one. The holiday resort of Muhandisin turned into a trap. Abu Bakr al-Firensi became more discreet. He had two wives. The Iraqi one was silent, but the French one grew impatient. From across the street, the neighbors could hear raised voices, until that day in June 2016 when the jihadist dragged his wife outside in the street and repeatedly kicked her. "She was shouting, 'Police, police,'" says Ziyad.

Al-Firensi accused the woman of denouncing him to hisbah, ISIS' implacable religious police. He had supposedly smoked during the Ramadan, a true sacrilege. A divorce was granted. The French wife disappeared.

A few days after the battle for Mosul began, on Oct. 17, 2016, Ziyad saw al-Firensi load up his BMW. He asked him whether he was going to Syria. "No, I want to die a martyr in Mosul," the jihadist replied, before blustering, "Keep an eye on the house while I'm away. Don't let anybody move in."

He left and never came back. After him, a pro-ISIS family from south of Mosul moved in. They finished plundering what was left. Then they too left, in January, as Iraqi forces approached. The neighborhood was liberated on Jan. 17.

The only thing that remains inside the house is an emptiness that seeps of despair, al-Firensi's drawings and five short texts written in June 2016 in a broken French on one of the walls. They belong to Oum Khaled, Abu Bakr's wife. Among other messages, she wrote, "Today my heart is finally appeased after these two months of torture because I'm headed towards the meeting with the all-merciful, finally. I feel light. Subḥān Allāh (glory be to God). It's near. Inch'Allah (God willing)."

See more from World Affairs here