KINSHASA — The deal to ensure peace in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is sealed, and everybody has signed on. Yet nobody is running out to celebrate. In the DRC, people, politicians and religious leaders know that any crisis resolution is generally considered a temporary thing.

There is little to fault in the text of the recent accord: It addresses all the points of dispute that had led the country to a situation one might call the nadir of its fortunes, if the DRC had not shown time and again that it can always sink further. For the Congolese, the first peaceful handover of power after a coup and a civil war cannot be taken for granted.

There is now, however, agreement on the crucial issue of a new time frame for presidential elections. It should have happened last November, but was cancelled for failing to be sufficiently organized in time. The election will now be held before "the end of 2017," and the sitting president, Joseph Kabila, is committed to not standing as candidate, respecting the Constitution's two-term presidential limit. It was the prospect of Kabila running again for his own office — which he had neither confirmed nor ruled out — which has recently been threatening the DRC with new upheavals. Kabila was supposed to have left office on Dec. 19, but on that day the capital was ominously silent, as if preparing for a fight. Riots had broken out earlier, killing at least 40.

Joseph Kabila with former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon in February 2016 — Photo: MONUSCO

In exchange for these overtures, the opposition has agreed that the outgoing president can stay in office until the new vote takes place. It has also won itself the prime minister's office within a caretaker, "cohabitation" government overseen by the National Transition Council (CNT) led by Étienne Tshisekedi, an aging opposition figure who retains political clout.

Higher powers

The deal appears balanced, ensuring nobody loses face or the chance to win power. But what's noteworthy is that the deal had to be negotiated, almost word by word, by the DRC's National Bishops' Conference (CENCO). "There was no other solution," one diplomat told us.

The Archbishop of Kisangani and CENCO president, Cardinal Marcel Utembi issued a communiqué to express his satisfaction at the "inclusive compromise" reached to avoid "chaos" in the country. This is hardly the first time the Church has played a central role in the DRC's public life. In a country where public services are lacking, the administration is largely absent and the army is under constant restructuring, the Church seems to be the last functioning institution. It runs schools and hospitals and has a network of priests keeping constant track of the states of this exhausted nation.

The Catholic Church is the only "structure that can today transmit and follow its decisions from its summit to the hierarchical base," Liège University professor Bob Kabamba said in a recent lecture. Certainly, evangelical churches have been gnawing away at the Catholic Church's dominance, but the influence it continues to exercise over 35 million believers is not in doubt, and grows whenever it must intercede with politicians, rather than God.

The Church's strength today largely revolves around one man: the highly respected archbishop of Kinshasa, Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo. The 77-year-old prelate, known for both his intelligence and formidable moral authority, was forced to take a clear political role in 2015 when President Kabila suggested he might hold onto power.

Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo (second from right) in Bruges in 2007 — Photo: Carolus/GFDL

Monsengwo firmly opposed "any constitutional revision or change to the electoral law." Four years before, he had notably declared that the disputed election results that made Kabila president were at odds "both with the truth and with justice." The president usually doesn't comment on the archbishop's declarations, but those around him let it be known that he does not like them. He once told a European diplomat the cardinal was his "main opponent."

In 1992, the Democratic Republic of Congo, which was then called Zaire, was sliding toward chaos. The regime of President Mobutu Sese Seko seemed exhausted, mired in economic problems and its own incompetence. While the rest of the continent was liberalizing, the DRC was seething with discontent. It agreed to adopt a multi-party system and formed a National Sovereign Conference (CNS) tasked with overseeing its transition, with Étienne Tshisekedi given an early leading role. As with last December, Cardinal Monsengwo and the CENCO were, naturally it seemed, asked to preside over the CNS.

But the aging Marshal Mobutu was loath to leave, and withdrew his commitments. The clergy resisted and called its flock onto the streets on Feb. 16. Their protests were brutally put down and Mobutu held onto power until 1997, when he fled as rebels advanced from the east. Then came a civil war in which millions died. Could the Church have prevented this? The cardinal once told the magazine Jeune Afrique that his role was "to pull on the rope without it giving way."

The Bishop v. Leopard Man

The struggle between Mobutu and the Church began early. On Nov. 24, 1965, when Mobutu, then a young colonel overthrew the DRC's first president, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, the people rejoiced. While Western powers were delighted with this vigorous anti-communist leader, Church authorities were distrustful. They regretted the passing of Kasa-Vabu, a faithful ally and former seminarian with whom they had worked in the struggle for independence. The clergy had managed to restore some of its tarnished standing from its longstanding proximity to Belgian colonial rule.

Mobutu did not trust the Church from the start. It was the only institution that might thwart his dream of absolute power, and it was not long before tensions turned to open confrontation. Mobutu's 1972 campaign to "Zairianize" the country and cleanse it of colonial influences was aimed directly at the Church. He changed his name from Joseph Désiré to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, or the "warrior who moves unstoppably from one victory to the next," and styled himself the Leopard Man.

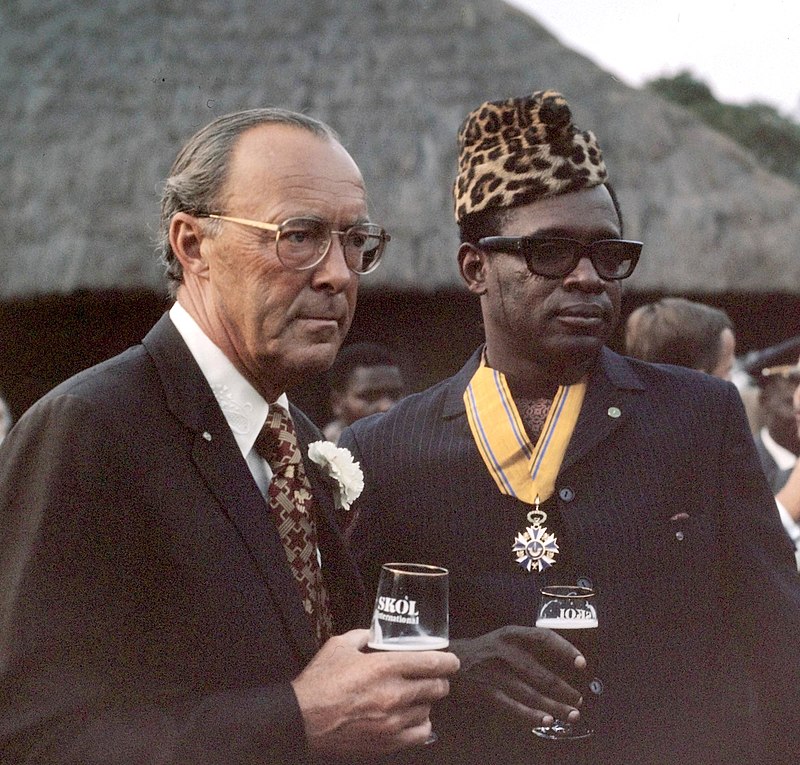

Mobutu Sese Seko with Dutch Prince Bernhard in 1973 — Photo: Dutch National Archives

With its systematic pillage and a fall in the prices of raw materials, the DRC sank into a prolonged recession. The misery this caused boosted the power of the local Catholic hierarchy, even if Mobutu sought in vain to confiscate its wealth in a bid to raise funds. Two visits by Pope John Paul II in the 1980s confirmed the Church's status as national counterweight to the power of the president-for-life.

While the Church has kept a critical posture toward politics throughout these years, and often avoided the worst for the Congolese faithful, its leaders have been unable, like other institutions, to lead the country out of its quagmire. The recent deal reached under its patronage in December could be its last. If it ultimately fails to make the Democratic Republic of the Congo a country with a semblance of a future, the Church too may lose its credibility.

See more from World Affairs here