ESPEJO — The meeting was fixed in a field of olive trees at noon, under 100 °F temperatures. The leaves of the shrubs, too small and too thin, offered little shade. Professor José Manuel Susperregui fusses around a table with a computer on it, as a sort of long fishing rod holding a camera is placed in front of him. The conference starts in front of a sparse audience: A few admirers are present, along with four or five journalists, the local mayor and a town councilor. It is here, in Espejo, about 25 miles away from Cordoba, that the professor is about to puncture a nearly century-old myth.

Susperregui meticulously and quietly strips down the most famous photograph from the Spanish Civil War, and a landmark in the history of photojournalism. Eighty-four years after it was taken, the professor says he has the proof, thanks to close observations and technical studies, that Robert Capa's legendary The Falling Soldier was staged.

"It is a fraud," he says. "No militiaman died in Espejo on the day Capa took this picture."

With his green shorts, beige shirt and sun hat, Susperregui looks like a 19th-century explorer. The 63-year old professor of Audiovisual Communications at the University of the Basque Country found what he believes to be the Holy Grail after seven years of research: the exact location where the photo was taken, which is different from where everyone had always believed it to be, and thus definitively incompatible with the story told by the photojournalism pioneer.

Until 2007, specialists of the photographer's work assumed that the picture was taken in Cerro Muriano, about five miles north of Cordoba. Capa's biographer Richard Whelan relied on the presence of the photographer and his wife, Gerda Toto, in Cerro Muriano on Sept. 5, 1936 when the leftist Republicans were defending the village from the attacks of the troops loyal to Francisco Franco.

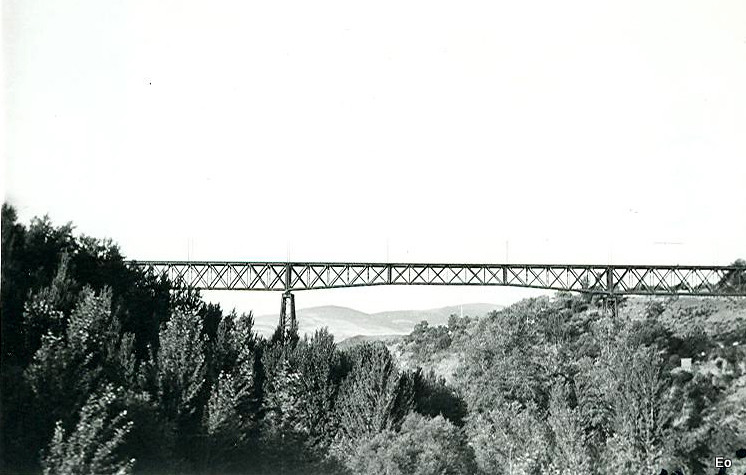

Bridge and mountain range in Cerro Muriano, Spain — Photo: Eladio Osuno

The photo — published for the first time in the French magazine Vu on Sept. 23, 1936 and then in the American magazine Life in 1937 — supported this assumption, as the vague landscape only fills the background of the snap. For the 60th anniversary of the photograph in 1996, Magnum Photos, the distributing agency of Capa's work, supplemented the official version through a press release: The identity of the soldier was discovered. He is Federico Borrell, an anarchistic militiaman killed on Sept. 5 in Cerro Muriano.

Stroke of luck

An irony of history is that it was information presented by Whelan that raised some of the deepest doubts. His 2007 book This is War! Robert Capa at Work revealed for the first time other photos belonging to the same series. Two new pictures came to complete the piece of landscape that appeared in the original photo. When the puzzle is assembled, a mountain range can be seen in continuity with the horizon. It was enough for many researchers to start looking for the actual location.

Susperregui's discovery is due to his determination but also to chance. After he realized the scenery was nowhere to be found in Cerro Muriano, he sent the three photos to the towns that were at war at the time when Capa was passing through the region. The series fell into the hands of a teacher who showed it to his pupils. One of the students recognized the Batan plateau. Susperregui crossed the area and found out three potential scenarios in Espejo at 30 miles away from Cerro Muriano. To identify the very place from which Capa took the photo, he wanted to simulate the shooting conditions. But the wheat fields from the 1930's have since been replaced by olive trees that now block the views of the mountains.

The professor therefore created an articulated arm equipped with lenses similar to Capa's and took photos from above the trees. He then came to the conclusion that The Falling Soldier was taken on the Cerro del Cuco ("the Cuckoo Summit") in Espejo, most likely on Sept. 3, 1936 as Capa and Taro were in Cerro Muriano beginning two days later. But this new version has a major problem: Espejo engaged in war only three weeks later.

Two villagers who were present in Espejo in 1936 denied that isolated scenes of combat happened before the great battle. Borrel, who died in Cerro Muriano, cannot be the one who appears on the picture.

"Robert Capa came to Spain to witness the war," Susperregui explains. "He went to Madrid, Aragon and Barcelona before coming to Andalusia. But he never got to find an active front and he realized that he could not go back home empty-handed. So he created a simulation." According to the professor, even the hill was used as a trick by Capa. "The camera leans at a 10-degree left bank angle, which reinforces the dramatic character of the photo."

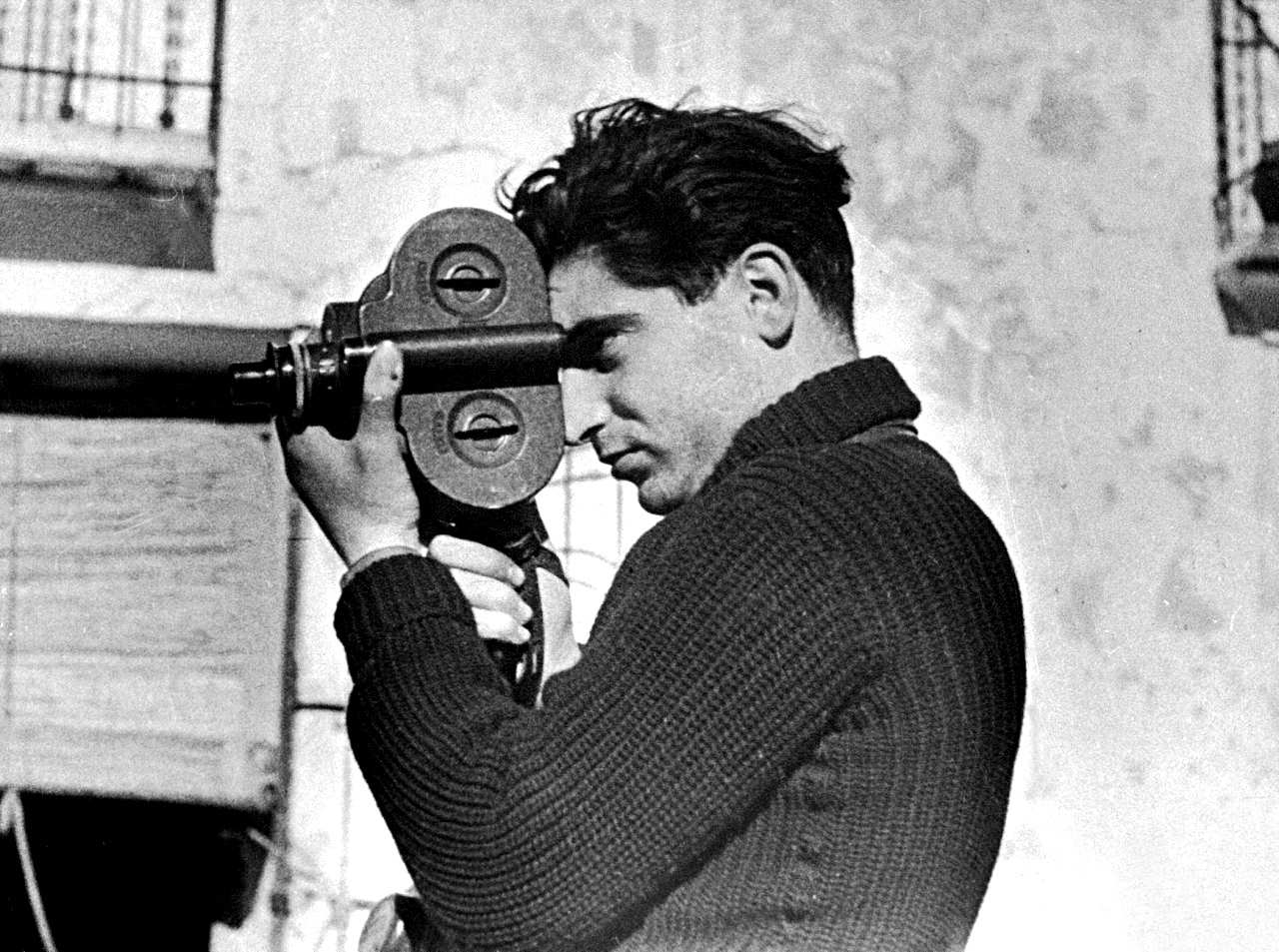

Robert Capa during the Spanish civil war, May 1937 — Photo: Gerda Ta

The staging theory upsets many admirers of Capa, who died in 1954 while covering the First Indochina War, at age 40. Miguel González, head of the Contacto agency, the Spanish partner of Magnum Photos, voices his opinion: "I talked with a specialist in stunts," González says. "If a militiaman could fake a fall so well, he would have made a fortune in Hollywood!"

Sign of a fist

One detail caught biographer Richard Whelan's attention: The soldier's clenched fist can be noticed under his left leg. Only a dead man could close his fist that way, as an actor would have had the reflex action of opening his hand to soften his fall. No, the discussion is nowhere near coming to an end.

New York's International Center of Photography, a museum that was founded by Capa's brother and that owns the image rights, has preferred not to get involved in the squabble. Cynthia Young, the curator of the Capa photographic archives, reacted to the recent findings: "In light of Susperregui's work, we believe that the photo was taken in the vicinity of Espejo," she says, adding that the identity of the soldier remains unknown. "Capa maintained that a group of militiamen were being trained when a soldier suddenly fell right in front of his camera."

This version contradicts other statements made by Capa himself between 1937 and 1947. In an interview for the New York World and in another for the WNBC radio ten years later, the photographer mentioned machine-gun fire by Franco's troops. The militiaman was trying to fire back when he was shot. "We don't really know what happened that day," Young concedes. "But what cannot be disputed is that when the film was developed, the soldier seemed to be dead."

Young notes that the photo began circulating in the international left-wing media to raise awareness of the cause of the Spanish Republicans. "It is one of Capa's most famous artworks," she adds. "And his talent keeps inspiring photographers and writers."